Shannon S. answered • 30d

M.S.- Neuroscience and Cognitive Sciences; 10+ years in the classroom.

When people talk about an analytical typology, they’re really talking about a thinking tool. It’s a way to organize messy social reality into categories that make patterns easier to see. The important thing, and this is where people often get tripped up, is that analytical typologies are not meant to describe the world exactly as it exists. They simplify on purpose. They exaggerate certain features and ignore others so we can analyze what’s going on without getting lost in the details.

This idea is closely tied to Max Weber and his concept of ideal types. Weber never claimed these types were “real” in the sense that you could walk outside and find a pure example. Instead, ideal types are intentionally clean, almost overdrawn models that help us compare cases and understand variation. Real life is always messier, and that’s expected.

A good analytical typology, then, isn’t judged by how accurately it mirrors reality. It’s judged by how well it helps us think. One of the first things it needs is clarity. The categories should be clearly defined, using a single organizing principle, so that the reader understands what distinguishes one type from another. If the logic behind the categories is fuzzy, the typology stops being useful pretty quickly.

Consistency matters too. All of the categories should be built using the same underlying logic. You can’t define one category based on motivation and another based on institutional structure and expect the typology to hold together. Strong typologies are internally coherent, even if reality isn’t.

There’s also the issue of separation. Analytically, the categories should be distinct, even if actual cases overlap. This is one of those moments where theory and reality don’t line up perfectly. The typology exists to give us contrast, not to perfectly label every example we encounter.

Finally, a typology has to actually do something. It should help explain differences, highlight patterns, or generate better questions. If it just names things without deepening understanding, it’s not doing analytical work.

Weber’s typology of authority is a good example of all of this in action.

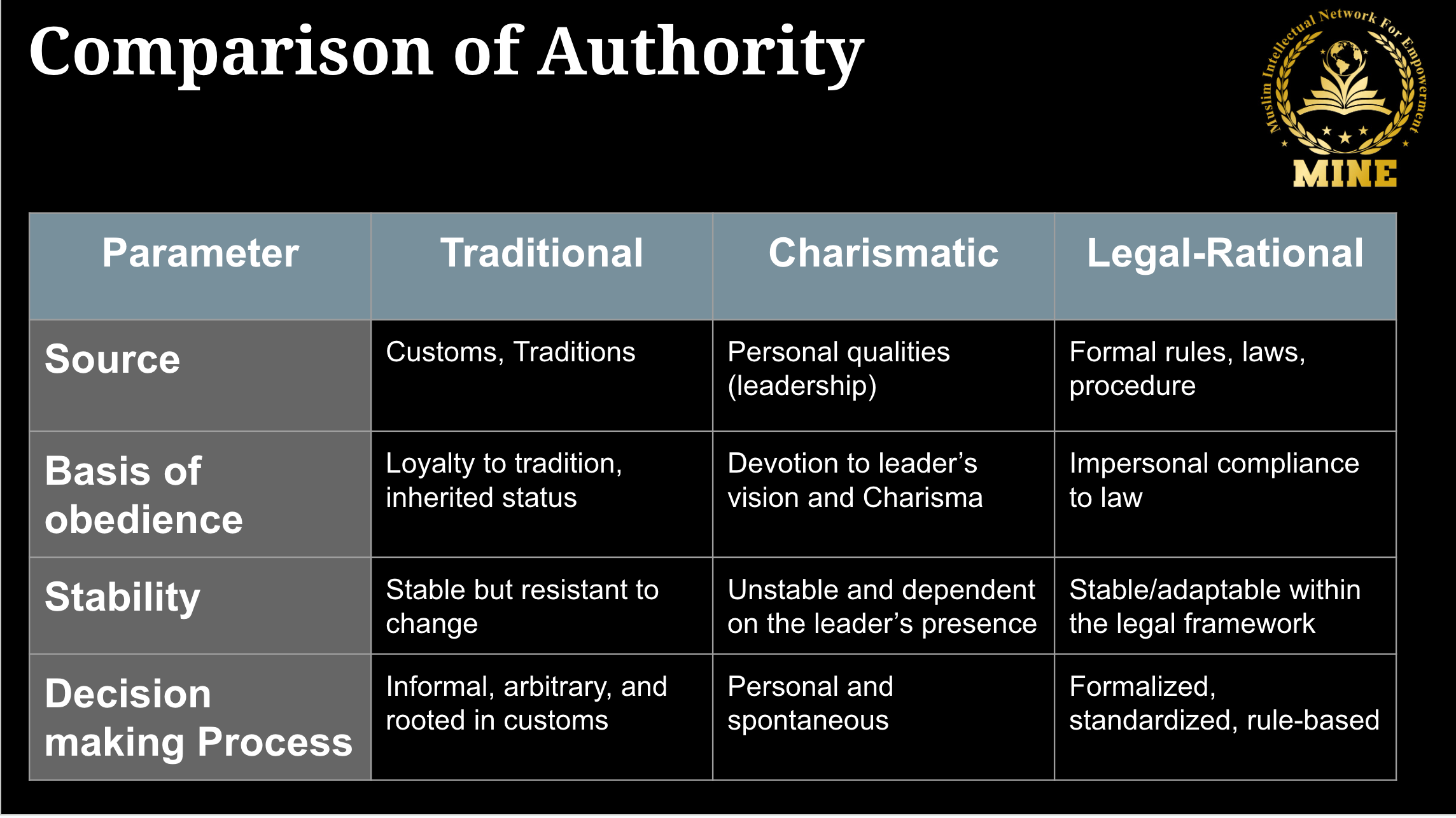

Rather than focusing on who holds power, Weber asked a more interesting question: why do people accept authority as legitimate? From that question, he identified three ideal types.

Traditional authority is based on custom and long-standing practice. People obey because that’s how things have always been done. Authority is tied to tradition, inheritance, or sacred history, and it’s often personal rather than bureaucratic.

Charismatic authority is very different. Here, legitimacy comes from the perceived extraordinary qualities of a leader. People follow because they believe in the individual — their vision, personality, or mission. This kind of authority can be incredibly powerful, but it’s also unstable, because it depends on continued belief in the leader.

Legal, or rational, authority is grounded in rules, laws, and formal procedures. Authority belongs to offices, not people, and obedience is owed to the system itself. This is the dominant form of authority in modern states, schools, and organizations.

What makes Weber’s typology work so well is that all three types are built around the same core idea: legitimacy. Each category explains authority using a different source of legitimacy, which keeps the typology conceptually clean. The types are analytically distinct, even though real governments and institutions almost always combine elements of all three.

By the usual criteria, Weber’s typology holds up extremely well. It’s clear, internally consistent, analytically distinct, and broadly applicable. More importantly, it’s useful. It helps explain why authority sometimes feels stable and routine, and why it sometimes collapses or transforms during periods of crisis.

Weber was also very honest about its limits. He never claimed that real-world authority neatly fits into one category. But that’s not a weakness, it’s entirely the point. The typology isn’t meant to classify reality perfectly. It’s meant to give us a sharper lens for understanding it.

Seen that way, Weber’s typology of authority isn’t just a “good” analytical typology. It’s one of the clearest examples of why analytical typologies are still used at all.

References

Weber, M. (1978). Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology (G. Roth & C. Wittich, Eds.). University of California Press.

Gerth, H. H., & Mills, C. W. (1946). From Max Weber: Essays in sociology. Oxford University Press.

Giddens, A. (1987). Social theory and modern sociology. Stanford University Press.